What if circular economy works local?

One Saturday in early June, a group of people gathered behind an old meatpacking plant on Chicago’s South Side, armed with shovels and handmade compost sifters.

In teams of three, the group began sifting a huge pile of rubble excavated from the lot in order to install an anaerobic digester. One person scooped rubble on to the screener, while the other two shook the screen back and forth, forcing small particles through while keeping large rocks and branches out.

“Soil has three components: Sand, silt and clay,” explained soil expert Dominic Brose as the group rested between bouts of sifting. “This is mostly sand we’re getting here. Hardly any clay.”

The setting was The Plant, a former meatpacking facility turned urban food hub. The occasion was Open Source Circular Economy (OSCE) Days 2015, a worldwide hack-a-thon aimed at inspiring people to reconsider waste, production and the economy as we know it.

Because Plant Chicago focuses on urban agriculture and material reuse, we decided to host an OSCE Days workshop with the challenge of building soil from all locally available materials.

We invited Brose, a soil scientist with the local wastewater treatment facility. He brought a 10-cubic yard load of composted wastewater solids (biosolids). We also had a truckload of woodchips dumped on site and set to work creating the sand portion of our soil recipe. With Dominic, a few Plant Chicago staff and six other workshop attendees, we sifted for two hours, yielding about a cubic yard of sand.

Estimating that the lot would need about 500 cubic yards of sand to meet our soil-building goals, we’d obviously need to innovate beyond hand-sifting. We spent the rest of the workshop brainstorming and drawing plans for building our own automated sifting machine from salvaged materials.

Defining the circular economy

Recycling woodchips, biosolids and sand back into soil certainly fits with the closed loop, waste-reuse tenants of the circular economy.

But reflecting on the event later, I couldn’t help but think that our soil-building workshop had demonstrated something more profound.

The circular economy concept has gained prominence in recent years, especially among sustainability professionals and companies with an environmental bent. It represents a world without waste by rethinking today’s make-take-dispose linear economy.

The Ellen MacArthur Foundation is the global voice behind much of the latest circular economy thinking. It defines the circular economy as “one that is restorative by design, and which aims to keep products, components and materials at their highest utility and value, at all times.”

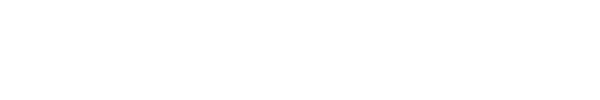

In our work at The Plant, imagining and building closed-loop systems of food production, we strive to follow the Ellen MacArthur Foundation’s five guiding principles:

- Design out waste;

- Build resilience through diversity;

- Work towards using energy from renewable sources;

- Think in systems; and

- Think in cascades

In our soil building effort, we focus on using byproducts traditionally seen as waste, including biosolids and excavation (construction) debris.

This effort is part of a much larger system of agricultural and food production happening at The Plant, which houses indoor and outdoor farms, a bakery, breweries and food distribution. The multitude of small business expertise and know-how in the building adds diversity and resilience. Finally, the building will operate using 100 percent renewable energy once the anaerobic digester is installed.

As our soil-sifting army toiled away under the sun, the word “local” also came to mind. What had motivated a group of volunteers and a soil scientist at one of the largest wastewater operations in the world to come out on a Saturday and sift through rubble?

If it was just the circular economy, they could have joined one of the many online OSCE Days forums or watched a TED talk from the comfort of their homes. Instead, they hopped on bikes and rode to The Plant to work alongside fellow Chicagoans committed to the same vision.

There are many ways to fold the concepts of community, teamwork and local action into the Ellen MacArthur Foundation’s principles, but these are not the focus of its work. Only three of the 26 case studies on the foundation’s site make mention of localized material sourcing and impacts.

While the circular economy is helping many companies and organizations to revolutionize their offerings, it doesn’t yet provide enough guidance for small businesses and communities.

Chicago’s local circular economy

There is need for a new level of nuance — a local circular economy — one, in which materials, ideas and feedback flow cyclically and locally.

We have a lot of inspiration to draw on in Chicagoland, where the reuse industry has experienced a mini-boom in recent years.

Inspired and aided by the success of building material reuse warehouses such as the Rebuilding Exchange, Cook County passed a demolition debris ordinance in 2012 requiring demolition and deconstruction contractors to meet a 70 percent material recycling target. More significant, contractors also must ensure that at least 5 percent of the demolition material is donated for reuse, a first-of-its-kind requirement for such ordinances.

Approval of the ordinance coincided with a surge of reuse activity around the city. Other reuse depots, such as the Evanston Rebuilding Warehouse and Repurposed Materials, have opened in the region. The Rebuilding Exchange offers a variety of workshops on woodworking and repurposing and runs a popular volunteer program.

In 2014, a group called The Young and the Reuseless also began leading monthly field trips to reuse sites around the city. The field trips are open to anyone, exposing the public to the inner workings of reuse warehouses, recycling facilities and remanufacturing centers.

When the local Reuse Alliance chapter and Plant Chicago teamed up to host Open Source Circular Economy events in Chicago, one larger company especially well known for its sustainability efforts chimed in: Method, a soap manufacturer that recently moved to Chicago.

When Method erected its factory on the south side (see pictures of the new green manufacturing hub), it used cradle-to-cradle principles to design the building structure and the manufacturing process. It also focused hiring efforts through community-based groups and gave preferential hiring to applicants from surrounding neighborhoods. This commitment is reflected in its circular economy definition:

“Method designs products for closed loop technical and biological cycles; commits equally to social and environmental benefit alongside making a profit; and pioneers the future by reinvesting in new technologies, materials and processes. We hope to create a model for other industries and to inspire more green manufacturing in Chicago.”

Meanwhile, in an older repurposed factory, The Plant is filling with small farmers and food businesses eager to try their hand at producing sustainably and locally.

Plant Chicago then works with The Plant community to conduct workshops on urban farming, run a volunteer program and farmers market and educate students and tour groups about the benefits of a local circular economy.

All of these examples are inspired by the idea of making the circular economy a reality, but their real power comes from the community. A local circular economy is how we save the planet not just for production, but for people.

Source: by John Mulrow – The circular economy’s missing ingredient: Local | GreenBiz